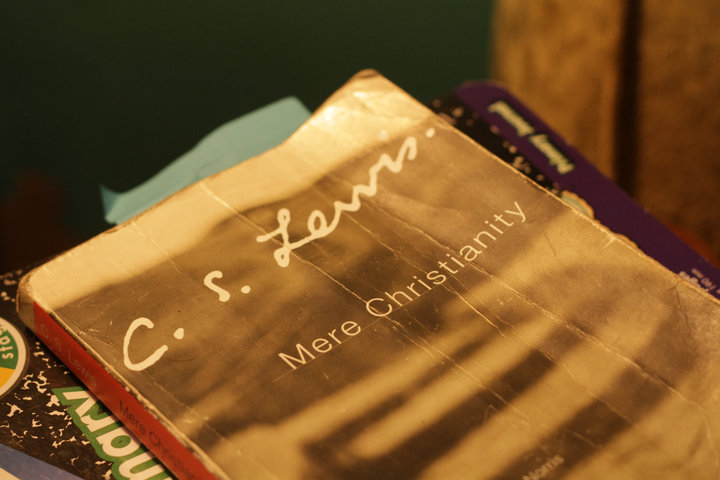

This month’s challenge started, and now ends, with C.S. Lewis.

Thirty days ago, I was challenged by a quotation from humanity’s favorite one-time-atheist-turned-Christian-writer-and-thinker in which he noted that he couldn’t imagine a man really enjoying a book and only reading it once. That sent me to the bookshelf where I pulled down my three favorite books, compiling their names into one conglomerate, super book title: Blue Like Irresistible Christianity. I started out with Donald Miller’s Blue Like Jazz, and then, due to some summer camps, took my precious time completing Shane Claiborne’s The Irresistible Revolution. Before I knew it, July 30th was upon me and I’d yet to open my third book, C.S. Lewis’ paramount work Mere Christianity. But I’ve never been one to give up easy – so I took a day off work, grabbed that last book and got to it. Keep calm and read on.

When I grow up, I want to be C.S. Lewis. Were he alive to read that last statement, no doubt he’d shudder, so let me clarify: I don’t worship the man (however great he was), but I certainly admire the gifts God blessed him with – a deep imagination, a calming presence, and a sound mind. Lewis had a God-given ability to take the profound and make it simple; to plumb the unfathomable depths of holy mystery and bring a snapshot back for those of us too scared to leave the shore. His words invite us all into the water, to swim beyond the point of comfort and safety, to venture out to where danger and faith are very much real. In my life, there’s been no writer (or thinker) as influential, life changing or eye opening as Lewis, so it’s only fitting that I close out my month of rereading with him.

Adapted from a series of radio addresses he gave on the BBC between 1942 and 1944, Mere Christianity actually consists of four separate books, each one subdivided into short chapters. Lewis begins with “Right and Wrong as a Clue to the Meaning of the Universe,” a short section in which he outlines his thoughts around human nature. Because humanity, across all religious and cultural lines, have similar understandings of right and wrong, Lewis believes we can attribute that to an outside Creative force (God, although does not call Him that at this point in the book). Book II, “What Christians Believe” and Book III, “Christian Behavior,” are my favorite sections; in them Lewis untangles two topics that can be disorienting even for seasoned veterans of faith. The fourth book, “Beyond Personality” offers Lewis’ insights into the doctrine of the trinity.

In the preface, Lewis explains his reason for undertaking the production of Mere Christianity. “Ever since I became a Christian,” he writes, “I have thought that the best service I could do for my unbelieving neighbors was to explain and defend the belief that has been common to nearly all Christians at all times.” He goes on to explain that the differences between denominations – something we focus on at our own peril – have “no tendency at all to bring an outsider into the Christian fold. So long as we write and talk about them we are much more likely to deter him from entering any Christian communion than to draw him into our own.” His goal, then, was to focus on and draw out that which is common between all believers – the mere Christianity that we all share. In so doing, he painted a most beautiful and compelling picture of the faith.

As this month (and challenge) ends, I must acknowledge two important lessons I’ve learned. First, I’ve been convinced that it’s always a good idea to reread a book, especially one that has been rather influential or significant in regards to your life or thinking. Reading these books once more has proved an encouraging venture, passions and ideas reawakened with each turn of the page. As a child, it was nothing to request the same bedtime story night after night until we could practically tell it ourselves; why should we treat the stories that influence us as adults any differently? Secondly, and perhaps more significantly, I’ve realized the power of shutting my own trap. When someone wiser speaks, its best to listen. So I’ll say goodbye to this challenge with a few quotations from Mr. Lewis’ masterpiece Mere Christianity. And please, if you haven’t read it yourself, go find it. Now.

See ya next month.

Fighting Religion:

“Christianity is a fighting religion. It thinks God made the world – that space and time, heat and cold, and all the colours and tastes, and all the animals and vegetables, are things that God ‘made up out of His head’ as a man makes up a story. But it also thinks that a great many things have gone wrong with the world that God made and that God insists, and insists very loudly, on our putting them right again.”

Learning:

“When you teach a child writing, you hold its hand while it forms the letters: that is, it forms the letters because you are forming them. We love and reason because God loves and reasons and holds our hand while we do it.”

Heaven:

“A continual looking forward to the eternal world is not (as some modern people think) a form of escapism or wishful thinking, but one of the things a Christian is meant to do. It does not mean that we are to leave the present world as it is. If you read history you will find that the Christians who did most for the present world were just those who thought most of the next. Aim at Heaven and you will get earth “thrown in”: aim at earth and you will get neither.

Heaven 2.0:

“If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.”

Lewis Burn:

“There is no need to be worried by facetious people who try to make the Christian hope of Heaven ridiculous by saying they do not want ‘to spend eternity playing harps.’ The answer to such people is that if they cannot understand books written for grown-ups, they should not talk about them.”

A Gift:

“Every faculty you have, your power of thinking or of moving your limbs from moment to moment, is given you by God. If you devoted every moment of your whole life exclusively to His service you could not give Him anything that was not in a sense His own already. So that when we talk of a man doing anything for God or giving anything to God, I will tell you what it is really like. It is like a small child going to its father and saying, ‘Daddy, give me sixpence to buy you a birthday present.’ Of course, the father does, and is pleased with the child’s present.”

True Life:

“Biological life and spiritual life is so important I am going to give them two distinct names. The Biological sort which comes to us through nature and which is always tending to run down and decay so that it can only be kept up by incessant subsidies from nature in the form of air, water, food, etc. is Bios. The Spiritual life which is in God from all eternity, and which made the whole natural universe, is Zoe. Bios has, to be sure, a certain shadowy or symbolic resemblance to Zoe: but only the sort of resemblance there is between a photo and a place, or a statue and a man. A man who changed from having Bios to having Zoe would have gone through as big a change as a statue which changed form being a carved stone to being a real man.

And that is precisely what Christianity is all about. This world is a great sculptor’s shop. We are the statues and there is a rumor going round the shop that that some of us are some day going to come to life.”

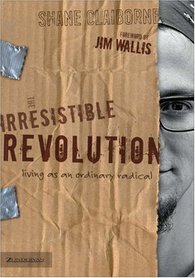

I finally finished. After a busy morning at church yesterday, I laid down on the couch, and through heavy eyes, finished The Irresistible Revolution. Just in time too – there are only two days left in July, and I have still an entire book to get through. This one’s gonna come right down to the wire.

At any rate, to close out my time with Mr. Claiborne’s opus, I want to offer a few more quotations for you to ponder. I’ve said it a few times already, but if you’ve never read The Irresistible Revolution, I strongly (and that word’s an understatement) recommend it. If you do choose to embark on that adventure, be sure to bring a highlighter – you’re going to need it.

Small Things:

If I had to sum up the nearly 370 pages of The Irresistible Revolution in one statement, it would be with this quote from Mother Teresa (who the author actually got to meet and work alongside before she passed away in 1997).

“We can do no great things, just small things with great love. It is not how much you do, but how much love you put into doing it.”

A simple lesson, yet one that would totally change the face of our world if we would choose daily to embrace it.

Hand and Feet: In 1st Corinthians Paul describes believers as the “body of Christ,” a metaphor that Christianity has clung to ever since. But to quote Spiderman (or more appropriately Socrates, from whom this quote seems to be derived), “with great power comes great responsibility.” Shane highlights this beautifully while remembering an old comic strip he once saw. He writes, “ two guys are talking to each other, and one of them says he has a question for God. He wants to ask why God allows all of this poverty and war and suffering to exist in the world. And his friend says, ‘Well, why don’t you ask?’ The fellow shakes his head and says he is scared. When his friend asks why, he mutters, ‘I’m scared God will ask me the same question.’” That’ll preach. And so will this song by Canadian rapper Shad (my new favorite). Pay careful attention to the last verse, I think it’ll sound familiar. Wretched and Beautiful: No introduction needed. “ The gospel is good news for sick people and is disturbing for those who think they’ve got it all together. Some of us have been told our whole lives that we are wretched, but the gospel reminds us that we are beautiful. Others of us have been told our whole lives that we are beautiful, but the gospel reminds us that we are also wretched. The church is a place where we can stand up and say we are wretched, and everyone will nod and agree and remind us that we are also beautiful.”

Ruined?:

Back in college, when I first read through The Irresistible Revolution, my dear friend Kristen (or Atlanta, as I still call her) and I did so together, exchanging lengthy emails about all the lessons God was “hitting us in the head with.”

That was five years ago, and since those days of living in dorms and eating at Commons, our lives have drastically changed. Kristen has a new last name, an amazing husband and a new life. I spent time teaching high school science before moving into youth ministry and am preparing to share my own last name with a remarkable lady in the next few months.

A few days ago, Kristen sent me those long-lost emails – it was like going back in time. I could feel the excitement (and fear) dripping from each word as we discussed (and even argued) about nearly every chapter in Shane’s book. When I was sending those emails, I thought I was so wise, on the cutting edge of Christianity. Rereading them (which is fitting given this month’s challenge), I came to stark revelation: my friend Kristen was the wise one. It seems fitting, then, to leave The Irresistible Revolution behind with a quotation gleaned from one our email correspondences, from August 20th, 2007. Through the lens of hindsight, her words feel powerfully prophetic.

“I know we've both said that this book (Irresistible Revolution) is ruining our lives. But here's another idea. Maybe, just maybe, we can live in joy with the fact that our lives are "ruined" by God. There are so many incredibly negative things our lives could be influenced and ruined by that, by comparison, being "ruined" by the creator of the UNIVERSE and the CREATOR of love, grace, hope, and joy seems not only a gift but an endowment. The fact that God entrusts anyone with anything is so completely overwhelming, much less him saying to ME "hey, you need to…[fill in the blank]". The idea that God, as big as he is, would entrust me, a complete and total sinner that could not HOPE to be worthy of his grace or love in the least, with something so huge as just existing is humbling.

Ultimately, I question the legitimacy of the word "ruined" in this entire context because of this thought: God is not actually ruining our lives, we are ruining our own by not following God's lead. We cannot ruin something that isn't ours because we don't know what the final picture is supposed to look like.

We are God's painting. When we lost touch with him, we became a mess. We became a mess because our life isn't ours, it's God's and God lets us come through by our individual paths he has decided for us. God knows EXACTLY what he's doing. Our lives are not being ruined by God. That is an unbelievably selfish thought, that my plans were ruined by the creator of everything. It's like saying "How DARE you, God?" and I hope I never have the gumption to even say that at all, much less without feeling some kind of guilt and regret in thinking that I know better than God. I do know that my heart is different than God's heart, and that my intentions are not his will. So while I may feel like he's ruining me, I'm actually ruining myself and his will for me. He has far greater things planned for me than I could EVER plan for myself and on that fact alone, I'm having to trust him. Terrifying stuff.

Back then God was radically changing our lives, and while the people and places may look different now, one thing remains the same: God continues to do his good work, and desires us to join Him in it – and that is the revolution that is so irresistible.

Long time, no blog – but I can’t say I didn’t expect it.

Before I even got my favorite books down off the shelf, I knew July’s summer rereading challenge was going to be difficult for one reason: summer camps. Things may slow down in other professions, but for youth ministers, the summer months fly by in a nonstop blur of sunburns, skits and silly songs. This month’s challenge started while on the beach with our high school students at a Christ in Youth conference in Florida. After returning, I read through Blue Like Jazz with all deliberate speed, starting my second book, The Irresistible Revolution, nearly a week later. I was making great progress when summer camp number two stopped me dead in my tracks. It was, however, totally worth it.

I’ve spent the past five days on the campus of the University of the Cumberlands, serving alongside some awesome high schoolers from our youth ministry as counselors for Camp UNITE, an anti-drug and alcohol summer camp for at-risk students from eastern Kentucky. Between visiting a water park, playing messy games, and making sure everyone gets enough to eat, I haven’t had much time to read or write. During a rare break in the action, however, I did manage to get through a few pages. I bumped into the following excerpt, and as a youth minister, found it very convicting.

Along with other believers, author Shane Claiborne visited Iraq during the 2003 bombings of Baghdad as part of a peace-making team. Upon returning, he writes, “a woman came up to me, pointed her finger in my face, and said ‘How dare you be so careless with your life and put your mother through all that? Jesus would be shaking His finger in your face, saying ‘how dare you be so reckless?’”

He continues, “I listened, silently, wondering what Jesus she was talking about. The Jesus who died on a Roman cross and invited His disciples to do the same? The Jesus who taught His disciples that if they wanted to find their lives, they should lose them? For centuries, Christians have been jailed, beaten and executed for preaching that Jesus. How was I to tell this lovely lady that Jesus was actually the one responsible for my traveling to Iraq?

I had a college professor who said, ‘All around you, people will be tiptoeing through life, just to arrive at death safely. But dear children, don’t tiptoe. Run, hope, skip or dance, just don’t tiptoe.’ In my youth-group days, I had seen all too many wild would-be Jesus radicals fall by the wayside because they had never been trusted with the adventure of revolutionary living. When I was a youth leader, one of the high school kids who had “given his life to Jesus” got busted only a few weeks later for having acid in school. I remember asking in disappointment, ‘What happened, bro? What went wrong?’ He just shrugged his shoulders and said, ‘I got bored.’

Bored? God forgive us for all those we have lost because we made the gospel boring. I am convinced that if we lose kids to the culture of drugs and materialism, of violence and war, it’ll be because we didn’t dare them… Kids want to do something heroic with their lives, which is why they play video games and join the army. But what are they to do with a church that teaches them to tiptoe through life so they can arrive safely at death?”

Wow. Am I pushing “my kids” to radically follow Christ, or just encouraging them toward a “safe faith?” The answer to that question is of extreme importance, and not just for the paid staff members of a church. Your life, your words, and your choices – no matter what profession you find yourself in – they’re all sending messages to those around you. As a follower of Christ, I pray that I can stop “neutering” the gospel in order to make it easier for others (or myself) to accept. Without the high challenge of Christ, we cannot truly be His disciples.

At any rate, that’s all for now. I’ve still got eighty pages to go before I can put down The Irresistible Revolution and move onto the final book of this month’s challenge. Time is not on my side.

God never ceases to amaze me; the way He ordains our lives, taking seemingly unrelated (even random) events and weaving them together into a beautiful storyline. He’s always doing this behind-the-scenes work, and for the most part, we just fail to recognize it. This week, however, He’s given me eyes to see – and I’ve been blown away.

I used to think I wasn’t important enough for God to communicate with. Don’t get me wrong, I knew He loved me (for the Bible tells me so), I just figured He had bigger fish to fry. He was probably too busy chatting it up with Billy Graham to speak into my life every single day. This year has changed all that. For the past twenty-three weeks, I’ve spent my Thursdays with a group of men committed to discipleship, men who believe that God is constantly speaking truth into each of our lives. With their guidance, and through taking intentional steps toward slowing down and quieting my life, I’ve begun to hear from the Almighty. It’s not an audible voice, not like talking with a friend over a cup of coffee – but it is just as intimate. God knows me – little, insignificant me – and He wants to get my attention. It still boggles the mind that the God who created waterfalls, black holes, and killer whales wants to have an ongoing conversation with me, and yet the more I learn to listen, the more I know this to be the truth. Talk about unmerited favor.

Last week, as I was trying to finish Blue Like Jazz, I got a text asking if I could take a group of students from our church’s youth ministry to a local homeless shelter. On the third Friday of every month, a group from our church takes a meal down to the Catholic Action Center and feeds 70-100 homeless/impoverished men and women. With the regulars out of town, I had been contacted in hopes of finding some replacements. Without thinking too much about it, my fiancé and I agreed. A few days later, I began to reread The Irresistible Revolution, and things started to to get interesting.

On Friday morning, I spent some time in my favorite reading place (that’s right, a cemetery) and came across a quote from Mahatma Gandhi that shook me to the core. Although not a believer, Gandhi’s life was much closer to the heart of Christ than many self-professed Christians, myself included. (It’s said – although hard to verify – that Gandhi often verbally professed admiration for Christ, but not Christians, whom he viewed as being unlike their Messiah.) While reading under the protective shade of a weeping willow tree, I came across the following paragraph in The Irresistible Revolution:

“I heard that Gandhi, when people asked if he was a Christian, would often reply,

‘Ask the poor. They will tell you who the Christians are.’”

Ouch.

After graduation, most of my college friends moved away, and I quit going to Phoenix Park, that corner of downtown where my life and the desperation of poverty would collide each weekend. Since then, I haven’t exactly ignored the poor, but I had lost my intentionality, that deliberate drive to, as Mother Teresa said, “meet Christ in all His distressing disguises.” Although I had agreed to visit the shelter over a week ago, it wasn’t until the morning of, just hours before I’d be pouring drinks and handing out pizza, that I began to recognize the hand of God in all this and to hear His call, once more, to care for “the least of these.” I had put it off for quite some while, and it was high time I got back on that horse.

Things went off without a hitch and I was feeling pretty good about myself as the men and women shuffled through the meal line. I had yet to realize, however, that this wasn’t the only reason God had me at the Catholic Action Center that night – He had more planned for me than just handing out cups of root beer. He had a message to get across.

He walked in late, wearing basketball shorts and a dirty white t-shirt. With nowhere else to sit, he pulled a chair up right beside the drink table where I was working. He introduced himself, and then promptly told me he’d died three times. I chuckled, but his face turned serious. “I used to be a teacher, man. Was crossing the street one day and BOOM!” After getting hit by a truck, he explained that he flat-lined and the doctors performed massive reconstruction on his body (he wasn’t shy about showing off his scars). The trauma had affected his mental capacities and he’d been unable to return to teaching. That was years ago – now he calls the streets home.

A former teacher myself, my dinner partner’s tale hit me right between the eyes. Maybe he was telling the truth, maybe not, but it didn’t really matter – God had my attention and wasn’t letting go. In an instant, I had gone from a place of pride, from seeing myself as the rescuer of these homeless men and women, to being thrown into the dirt alongside them. Life was fragile, and but for the grace of God, that could have been me walking into the shelter that night. I may have brought these men and women dinner, but God was showing me that I was nothing more than a beggar showing another beggar where to find bread.

I work at a well-to-do church, one that is generous enough to allow me to live in a house on their property. On all sides of me are nice neighborhoods, massive houses, and expensive cars. I had agreed to visit the Catholic Action Center in order to see poverty, to be able to follow Christ’s command to care for those affected by it. But as I drove home that night, I realized poverty isn’t just contained to 5th Street or Martin Luther King Boulevard – its all around me, even in the deed-restricted communities. These neighborhoods might not have a shortage of money, they are full of loneliness, materialism, broken hearts… the list goes on and on. Poverty infects everything, no matter where we live.

Praise God, then, that one of Christ’s first public sermons finds Him declaring his mission to “preach the Good News to the poor, to announce forgiveness to the prisoners of sin and restore sight to the blind, to forgive those shattered by sin, and to announce the year of the Lord’s favor.” And that’s life-changing news, whether you live under a bridge or in Andover Forest.

In only one day of reading, I’ve managed to breeze through nearly one-hundred pages of Shane Claiborne’s The Irresistible Revolution. As if that first sentence didn’t make this incredibly obvious, let me say for the record that even on the second read-through this book is hard to put down. While reacquainting myself the familiar stories, I was reminded of the hours I’d once spent under the shade of a tree behind the Blanding II residence hall on the University of Kentucky’s campus, reading till my eyes hurt. I kept telling myself I’d stop at the end of the next section. I never did.

The Irresistible Revolution follows Shane Claiborne’s lifelong search for a “real Christian,” a quest that took him from the comforts of east Tennessee to the slums of Calcutta and back again. Along the way, he stays with lepers, interns at one of America’s most prominent megachurches, and stands beside homeless mothers facing eviction – a compelling story that tugs at the heart from page one and won’t let go.

Obviously, Shane can tell his story much better than I can, so I’m going to do my best to get out of the way and let him do some talking (or writing, as it were). Below are three of my favorite quotations from the first few chapters of The Irresistible Revolution, as well as a song and a little commentary from me sprinkled on top. Perhaps it will encourage you to investigate this irresistible revolution for yourself.

Søren:

If I had to sum up Shane’s philosophy of life in one sentence, I’d be this: Jesus meant what He said. The author dares to believe that when Jesus said, “Blessed are the poor,” He actually meant (this may be shocking, so prepare yourself) “blessed are the poor.” And when Jesus told the rich young ruler to “sell everything he had and give it to the poor,” He wasn’t teaching a veiled lesson on materialism, but actually wanted this young man to sell his earthly possessions.

Along with Shane, I’ve watched myself grow very disenchanted with Christian scholarship that attempts to make the words and commands of Christ “safer.” God didn’t send His son to this planet so that we could be comfortable, but rather to lead us back down the narrow path to redemption. C.S. Lewis’ description of Aslan in The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe remains one of my favorite portrayals of Christ – when asked by a newcomer to Narnia if the great lion was safe, Mr. Beaver answered, “Who said anything about safe? ‘Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the king, I tell you.” When we realize that Christ was serious about His followers loving their enemies, putting themselves last, and caring for the least of these, the words of the scripture may become less comforting, but they’ll be no less true. And even more than comfort, we need the truth.

In explaining his feelings on this topic, Shane quotes from Danish philosopher and theologian Søren Kierkegaard. I pray you find this excerpt both as amusing and challenging as I do.

“The Bible is very easy to understand. But we Christians are a bunch of scheming swindlers. We pretend to be unable to understand it because we know very well that the minute we understand we are obliged to act accordingly. Take any words in the New Testament and forget everything except pledging yourself to act accordingly. My God, you will say, if I do that my whole life will be ruined. How would I ever get on in the world? Herein lies the real place of Christian scholarship… the Church’s prodigious invention to defend itself against the Bible, to ensure that we can continue to be good Christians without the Bible coming too close. Oh, priceless scholarship, what would we do without you? Dreadful it is to fall into the hand of the living God. Yes, it is even dreadful to be alone with the New Testament.”

Miracles: Two nights ago, I had the privilege to preview a new, upcoming documentary entitled “ Father of Lights.” It doesn’t release to the general market until October, but if you get a chance to see this film, please don’t pass it up. In a word, it’s mind-blowing. The filmmakers set out to show that God, the Father of Lights, continues to shine His love even in the darkest places on Earth. What follows are storylines that seem to have been lifted straight from the book of Acts. A believer in India wakes up every morning with no agenda, waiting on the voice of God to reveal his plans for the day – confronting a dangerous witchdoctor, preaching the gospel in remote Hindu villages, or tracking down a man shown to him in a vision. Another segment tells the story of a well-to-do American family who gives up everything to follow God to China, eventually becoming the caretakers of a large orphanage for abandoned children with physical and mental disabilities. A third segment follows a believer as he prays for and heals (through the power of God, of course) people on the streets of Jerusalem. It’s nothing short of incredible. The next morning, with thoughts of those miracles and examples of radical obedience still fresh on my mind, I ran across the following quotation, one that helped to put it all into perspective. Do I believe in a God of miracles? Yes! Do I think they still occur today? Absolutely! And yet, I’m guilty of experiencing the biggest miracle of all on a daily (maybe hourly is more accurate) basis without even noticing it. Amazing love, indeed. “I started to see that the miracles [of Christ] were an expression not so much of Jesus’ mighty power as of His love. In fact, the power of miraculous spectacle was the temptation He faced in the desert – to turn stones to bread or to fling Himself from the temple. But what had lasting significance were not the miracles themselves but Jesus’ love. Jesus raised His friend Lazarus from the dead, and a few years later, Lazarus died again. Jesus healed the sick, but they eventually caught some other disease. He fed the thousands, and the next day they were hungry again. But we remember His love. It wasn’t that Jesus healed a leper but that He touched a leper, because no one touched lepers. And the incredible thing about that love is that it now lives inside of us.”

Worship Or Imitation:

I find the following quotation incredibly convicting. I pray I’m not alone in that.

“I did a little survey, probing Christians about their (mis)conceptions of Jesus. It was fun to see how many people think Jesus loved homosexuals or ate kosher. But I learned a striking thing from the survey. I asked participants who claimed to be “strong followers of Jesus” whether Jesus spent time with the poor. Nearly 80 percent said yes. Later in the survey, I sneaked in another question. I asked this same group of strong followers whether they spent time with the poor, and less than 2 percent said they did. I learned a powerful lesson: We can admire and worship Jesus without doing what He did. We can applaud what He preached and stood for without carrying about the same things. We can adore His cross without picking up ours. I had come to see that the great tragedy in the church is not that rich Christians do not care for the poor but that rich Christians do not know the poor.”

Hard Luck & Heart Attack:

Some of my favorite writers write songs. Among those, the top three (which is actually four) are:

1) Bob Dylan (obviously)

2) Derek Webb and Bill Mallonee (it’s a tie!)

3) Ben Gibbard (of Death Cab for Cutie)

Around the same time that The Irresistible Revolution was ruining my life for the first time, I discovered Bill Mallonee and his band, Vigilantes of Love, in the used section of CD Central. A sticker on the cover compared him to Dylan (see #1 above), so I took the bait. Am I ever glad I did! That album, Audible Sigh, contains one of my favorite songs, one that’s always reminded me of the themes explored in The Irresistible Revolution. I’m not sure they’ve ever considered making Shane’s opus into a film, but if they ever do, this song is a must for the soundtrack – in my humble opinion, of course.

After a brief reading break, the “Blue Like Irresistible Christianity” train is back on the track, setting its sights once more on this month’s challenge – to reread the three most influential books in my life. I’ve left station one, Blue Like Jazz, in the dust, and have set my sights squarely on the second leg of this journey.

A few years ago, as a graduate student at the University of Kentucky, I was part of a small but dedicated band of students who spent their Friday nights at Phoenix Park in downtown Lexington. In years past, this area had been the site of the grand Phoenix Hotel, the epicenter of the city’s nightlife. A symbol of glitz and glamour, the hotel was in operation for over 150 years, housing everyone from Civil War generals to movie stars and everything in between. It was finally razed in the 1980’s to make room for a skyscraper – however, in a move that was eerily repeated in 2008 with an entire block of downtown Lexington (including beloved concert venue and bar The Dame) construction on the proposed building never began. After years as an empty lot, the area was turned into a public park.

Things have drastically changed at the Phoenix. At one time the hub for social life in Lexington, the park named in the hotel’s honor attracts a much different crowd today – namely scores of the city’s homeless population. And this is precisely why ten or so UK students would walk over a mile to that park every Friday night. On the way, we’d pool our money together, stopping at McDonalds to order as many cheeseburgers as we could afford. Our homeless friends (and that’s exactly what they were) knew we’d be coming, and would start gathering as the sun began to set. Believe me, it didn’t take long to hand out those twenty or so cheeseburgers. As they ate, we’d catch up on their lives. Sometimes we’d pray, other times we’d just sit and talk. As the weather began to turn cold, we’d pack along extra sweatshirts, socks and mittens. And once, to the chagrin of my mother, I even bought a case of cigarettes for my friends and passed them out.

As compassionate as that story may make me sound, I’ve gotta be honest – I initially joined up with that Friday night crew for one reason only: a girl. She didn’t know that, and I never told her either. It’s actually kind of embarrassing to admit that now, and as you can guess, things didn’t work out with her – that, however, didn’t stop my heart from being changed. I began to look forward to Friday nights and seeing my friends once more. I learned their names and stories, laughing when they laughed and crying when they cried. When the weather turned bad, my first thought was their comfort and safety. For the first time in my life, my heart was learning to beat for someone other than myself.

My friend Dave, who lived in the dorm next to mine, was a regular with the Phoenix Park crew. As we walked home one Friday night, he caught up with me: “Look man,” he said, “I’ve been reading this book and you’ve got to pick it up. Seriously, it’s ruining my life – in the best way possible.” It’s hard to argue with that kind of endorsement.

Little did I know, as I drove to the Christian bookstore later that weekend, that what Dave said about his life would soon be true of mine as well. That little book, Shane Claiborne’s The Irresistible Revolution, would make a complete wreck of the life I’d planned for myself. Thrown out the door were assumptions of comfort and ease; new cars, nice clothes and big houses. In its place something brand new was growing, something much closer to the heart of God.

In Blue Like Jazz, author Donald Miller writes that he learned an important lesson from his friend, Andrew the Protestor. “What I believe is not what I say I believe,” he writes, “[but rather] what I believe is what I do.” As a freshman in college, when I first read Blue Like Jazz, it spoke deeply to my heart, addressing my need for faith and its role in my life. Four years later, when The Irresistible Revolution came along, the soil of my soul was once more fertile for reformation, and this book became the seed. Through it, God got my attention: it was time to move, time for what I believed to become so much more than just empty words. It was time for my faith to migrate, to make the trip out of my heart and into my hands.

And that was only on the first read through – who knows what God’ll say the second time around. But you can be sure of one thing: I’ll be writing it down this time.

The past two days have been a reading frenzy. Believe it or not, I actually did the math before I started – in order to meet July’s challenge, to reread my three favorite books, I’d need to finish one every ten days or so. What I failed to account for, however, was the fact that I’d be spending the first six days of July in Panama City Beach, Florida, with our high school youth group as we attended the Christ in Youth conference. Believe me, I’m not complaining – the beach, the teaching and worship experiences, and most of all, the quality time with those kids, was awesome. Unfortunately, the company of nearly 700 high school students from Kentucky, Illinois and Texas is not the best place to get some serious reading done.

I finally started Blue Like Jazz on our last day at the beach, finishing exactly one chapter with the few minutes of solitude I found while walking the coastline. And although I managed to knock a few more chapters out on our brutal fourteen-hour bus ride home, I’ve breezed through the majority of the book in the past the five days. Yesterday afternoon, with a few hours to spare, I set up camp under the shade of a majestic tree on the edge of a country church’s cemetery. If you haven’t tried reading in a cemetery, I highly recommended it. Maybe it’s just me, but I find them very peaceful. Plus, I know I won’t be interrupted.

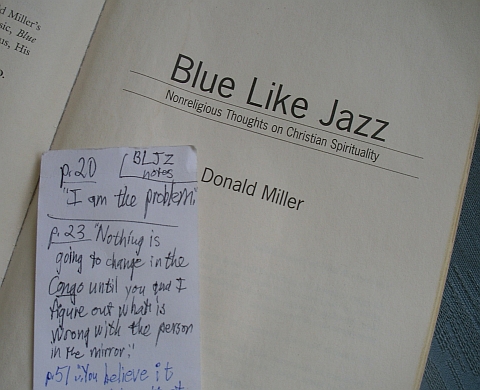

My second time through Blue Like Jazz has been just as exhilarating as the first. When I was introduced to this book, back in college, I couldn’t put it down – I ended up flying through this memoir-like collection of essays in no time. And although I put myself under a bit of a time crunch this time around, I still managed to read it slower, more deliberately, giving myself time to really chew on and digest Miller’s words – and just like the first time around, I found them as fulfilling as Sunday dinner.

If you haven’t read Blue Like Jazz, or any of Donald Miller’s other fantastic works, I hope you’ll consider doing so. He offers a fresh, humorous, yet exceedingly honest take on what it means to follow Christ. You won’t find any buzzwords here, no plan to sell, no five-step method to eternal happiness – just a guy being real about what he knows to be true, even if he can’t explain it all the time.

I figure the best way to end my stint with this outstanding book is to let Don do the talking. Below are a few of my favorite quotations (plus a little extra commentary from me on the side) – I hope they inspire you to pick up this book for the first (or even second time). Heck, I’ll let you borrow my copy – I’m done with it. For now.

Belief:

“Tony and I were talking about belief, what it takes to believe, and he asked me how I believed in God. As I said before, it feels so much more like something is causing me to believe than that I am stirring up belief. In fact, I would even say that when I started in faith I didn’t want to believe; my intellect wanted to disbelieve, but my soul, that deeper instinct, could no more stop believing in God than Tony could, on a dime, stop being in love with his wife. There are things you choose to believe, and beliefs that choose you. This was one of the ones that chose me.”

There have been times in my life when this paragraph has described exactly the way my soul feels. In fact, rereading it took me back to my freshman year of college, when as a biology major my faith was coming under fire in nearly every class I attended. There were times when my brain wanted to stop believing, and yet I could not – I felt, as Don writes, that God had chosen me (instead of it being the other way around). And for a kid trying to exert his freedom, that feeling could be mighty annoying.

Grace:

“I was a Fundamentalist Christian once. It lasted a summer. I was in that same phase of trying to discipline myself to “behave” as if I loved light and not “behave” as if I loved darkness. I used to get really ticked at preachers who talked too much about grace, because they tempted me to not be disciplined. I figured what people needed was a good kick in the butt. I believed if word got out about grace, the whole church was going to turn into a brothel. I was a real jerk, I think.”

This statement makes me both laugh and cry. I laugh because I totally identify with it – I distinctly remember, as a high school student, lying on my bed and coming to the realization that Christianity was actually pretty easy. All it really came down to was making the right decisions, and I was disciplined enough to do that. Fifteen-years old and I already had this whole thing licked! Friends would come to me asking for my advice with their “struggles,” and I always told them the same thing: stop doing wrong! I cry, though, because like Don, I’m pretty sure I was a jerk to those friends who only needed to be loved. Growing up, I’ve discovered I’m not as disciplined as I once thought, that grace can be beautifully life changing, and that when you follow Christ you’ll hardly find yourself walking down easy street.

Andrew:

“Andrew taught me that what I believe is not what I say I believe; what I believe is what I do.”

Amen.

The Cool Christian:

“I had this idea once that if I could make Christianity cool, I could change the world, because if Christianity were cool then everybody would want to deal with their sin nature, and if everybody dealt with their sin nature then most of the world’s problems would be solved. I decided the best way to make Christianity cool was to use art.”

This reminds me so much of myself. In college, I got the idea that if Dave Matthews finally bit the bullet and become a full-on Christian, then great revival would surely sweep through the land. I mean, he was nearly half way there already, what with missionary parents and all those songs about God. I could just see all the hippie, pot-smoking, hacky sack kids coming to Christ in droves – he might even give Billy Graham a run for his money. I thought about writing him letter to convince him of this fact, but I chickened out, so I settled on the next best thing. I decided I’d pray until Dave became a card-carrying Christian (I’m not sure how I’d known when my prayer was answered. I guess I thought he’d hold a press conference or something.). I lasted about a week. But sometimes, when I’m listening to his music, I’ll still throw another prayer up – not in hopes that Dave’ll lead us to the Promised Land, but that, by the grace of God, he’ll find his own way there.

Women:

“Here’s a tip I never used: I understand you can learn a great deal about girldom by reading Pride and Prejudice, and I own a copy, but I’ve never read it. I tried. It was given to me by a girl with a little note inside that read: ‘What is in this book is the heart of a woman.’ I am sure the heart of woman is pure and lovely, but the first chapter of said heart is hopelessly boring. Nobody dies at all. I keep the book on my shelf because girls come into my room, sit on my couch, and eye the books on the adjacent shelf. You have a copy of Pride and Prejudice, they exclaim in a gentle sigh and smile. Yes, I say. Yes, I do.”

That’s for my fiancé. And its just plain hilarious. And true. Oh, so true.

Selfishness:

“The most difficult lie I have ever contended with is this: Life is a story about me.”

Although I know the truth, I still find myself fighting that lie nearly every day of my life.

The Holiness of God:

“I was talking to a homeless man at a laundry mat recently, and he said that when we reduce Christian spirituality to math we defile the Holy. I thought that was very beautiful and comforting because I have never been good at math. Many of our attempts to understand Christian faith have only cheapened it. I can no more understand the totality of God than the pancakes I made for breakfast understand the complexity of me. The little we do understand, that grain of sand our minds are capable of grasping, those ideas such as God is good, God feels, God loves, God knows all, are enough to keep our hearts dwelling on His majesty and otherness forever.”

Amen. Again.

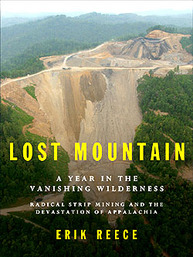

Lost Mountain should be required reading for every Kentuckian. Penned by University of Kentucky journalism professor Erik Reece, it recounts his year spent visiting the eponymous mountain in eastern Kentucky as it was slowly dismantled through a radical strip mining procedure known as mountaintop removal. He not only describes the environmental devastation in great detail (the clear-cutting of trees, poisoning of water sources, and the loss of species), but the human effect as well – exploited workers, cancer levels off the charts, grassroots protest movements, rapacious coal barons and the senators who turn a blind eye toward them. Mountaintop removal isn’t a regional problem restricted only Appalachia – it’s an issue that affects every citizen of our nation. With nearly half of all American electricity being generated by the burning of coal, there’s a great possibility that the lights in your home and the computer you’re using to read this blog are connected to the destruction of some of America’s oldest forests and mountains. (Ignorance is not bliss - click here to learn if your electricity provider purchases coal from mountaintop removal sites.) Lost Mountain is a big reason why I’m so passionate about the issue of mountaintop removal to this day – a close friend and I even marched on the state capitol this past February, with temperatures just above freezing, to show our support for ending this devastating practice. Because his last work was so influential, I was more than excited when that same protest friend loaned me Reece’s newest book, a 2009 publication entitled An American Gospel. A deeply personal work, Reece discusses the effect religion has had on his family, including the suicide of his father, a Baptist minister, at thirty-three years of age. A small child at the time, Reece was left to the care of his paternal grandparents, his grandfather a fundamentalist Baptist preacher in rural Virginia. The author places most of the blame for his father’s depression and suicide on two things: bipolar disorder and Christianity. He believes that, unable to meet the demands of the faith, his father slipped deeper and deeper into the depression that eventually led him to end his life. An American Gospel is an anti-conversion story, a coming-of-age tale in which the author leaves behind the faith of his fathers in order to embrace a new gospel, one heavily influenced by American writers such as Walt Whitman, William Byrd, and Thomas Jefferson. Near the end of his life, the third president of the United States constructed his own version of the Bible by cutting and pasting sections from the original work. The Jefferson Bible, as it’s since become known, is notable for what it excludes from the original narrative – namely the supernatural elements: miracles, claims to deity and the resurrection. This work, in which Jesus is nothing more than a man with great insight, is the primary text for Reece’s newfound faith. The author’s thinking was also heavily influenced by time he spent studying at a Buddhist monastery. Reece’s biggest hang-up with Christianity is its view of humanity – that mankind is inherently sinful, broken, and in need of a Savior, believing this to be the slippery slope upon which his father fell. The Eastern philosophy of Buddhism offered Reece a welcome counterpart, teaching that man is born inherently good, with the potential to reach enlightenment. Upon this base he added works like Whitman’s “Song of Myself” to craft a gospel around the idea that humanity has no need for redemption or a Savior.

In Blue Like Jazz, author Donald Miller paints a very different picture of mankind. Although certainly not experiencing the trauma of a parental suicide, Miller’s own father was also absent. Growing up in a single parent home in Texas, Miller regularly attended church, but in light of his situation, had little motivation to know a God who described himself as Father. In fact, he writes that he pictured God as a “slot-machine,” doling out good and bad based upon our actions. Miller’s god was more math equation than deity, and that was all well and good, at least for a little while. As he grew into a teenager, Miller found that he couldn’t ignore the fact that there were major problems with the world – and those problems might even be inside him.

“I started to sin about the time I turned ten,” he writes. “I believe it was ten, although it could have been earlier… ten is about the age a boy starts to sin. Girls begin to sin when they are about twenty-three or something.” It started small – lying, cusswords, mischief. He had his first encounter with guilt after he found a discarded Playboy near the railroad tracks where he often played. He slowly flipped through the pages, digesting and storing each image in his mind. He remembers, that night, feeling for the first time that his life “had become something to hide.” He goes on to recount the story of the Christmas when he spent the majority of his money on a fishing pole for himself. With the leftover change, he purchased his mother a book on a subject she cared little about it. He writes that, by that time, “the guilt was so heavy that I fell out of bed onto my knees and begged, not a slot-machine God, but a living, feeling God to stop the pain.”

He goes on, “I knew there was something wrong with me. And I knew it wasn’t only me. I knew it was everybody. It was like a bacteria or a cancer or a trance. It wasn’t on the skin; it was in the soul. It showed itself in loneliness, lust, anger, jealously, and depression. It had people screwed up bad everywhere you went – at the store, at home, at church; it was ugly and deep… I was just a kid so I couldn’t put words to it, but every kid feels it.”

Don writes that he was reminded of these early feelings after watching news coverage of human-rights atrocities in the Congo. Later that night, he was explaining the situation – an entire village raped and murdered – to his friend Tony the Beat Poet. Don was commenting that he couldn’t believe anyone could do such a thing when his friend turned the tables on him. “Do you think you could do something like that, Don?” he asked. When Don answered an emphatic (and slightly-offended) “no,” Tony probed further: “What makes those guys over there any different from you and me?” It was a question that stopped Don, and me as I read last night, dead in our tracks.

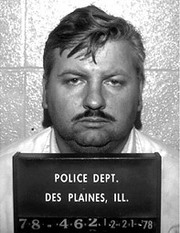

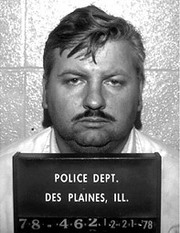

I know this sounds weird, but I’ve thinking about John Wayne Gacy a lot lately. He grew up in Chicago, in the 1940’s, under the terror of an alcoholic and abusive father – a man who constantly beat and berated his son. Although he spent his childhood trying to please his father, Gacy was continually told that he’d never amount to anything, that’d probably grow up to be a “queer.” No matter how hard he tried, Gacy couldn’t win the affection of his father. Years later, that boy would become one of Chicago’s most notorious serial killers. Over the span of six years, from 1972-1976, he’d sexually assault and murder at least thirty-three teenage boys and young men. Gacy is known for two horrific details: 1) He often dressed up as a clown, whom he named Pogo, to entertain children at festivals, parades and parties and 2) He hid the majority of his murder victims near or around his suburban home, twenty-six of which were found buried in the crawl space beneath the house. He was an appalling man, responsible for some of the most heinous crimes in the history of America.

My fiancé, who’s much cooler and indie than I am, recently introduced me to Sufjan Stevens, a singer-songwriter who may be the most creative musical artist I’ve ever heard. His 2005 masterpiece (and I don’t use that term lightly) Come On, Feel the Illinoise, is a concept album highlighting the characters, stories, and towns of our nation’s 21st state, Illinois. The fourth song on that album is named after Chicago’s most infamous serial killer, telling the story of John Wayne Gacy from childhood, when an accident caused a blood clot to form in his brain, “His mother cried in bed / folding John Wayne’s t-shirts / when the swing set hit his head;” to the murders, “He dressed up like a clown for them / he’d kill ten-thousand people / with a slight of his hand;” to his eventual capture, “look underneath the house there / find the few living things, rotting fast.”

Despite the macabre topic, it’s the last two lines of the song that remain with the listener long after the music fades. After describing the grim history of John Wayne Gacy for nearly three minutes, Stevens finishes by admitting, “in my best behavior I am really just like him / look beneath the floorboards for the secrets I have hid.” The first time I heard those lines they literally stopped me in my tracks.

And so here I am, torn between two extremes. On one side, a local, respected author tells me that, at my core, I’m good and have no need for a Savior. On the other side, a writer claims all of humanity is broken and standing beside him, a songwriter is comparing himself to a serial killer. So which is it? Both of these opinions, these opposite ways of viewing humanity, cannot be true. It must be one at the expense of the other.

Looking at the world around me, but even more so, turning that gaze inward toward myself, I can’t do anything but agree with the observation of God, made only six chapters into the story of the Bible: “The LORD saw how great the wickedness of the human race had become… that every inclination of the thoughts of the human heart was only evil all the time.” It doesn’t take me to long to pinpoint selfishness, impatience and greed within myself. Digging a little deeper I find resentment, lust, and anger. And so I have to come to the same conclusion that Don Miller and his friend Tony reached after discussing the atrocities of the Congo – that raised under different circumstances, say in the bush where I was taught that other ethnic groups were inferior, I too could perhaps be capable of raping and burning an entire village to the ground. Or had I been born into a home with an abusive, sadistic father, who’s to say that I myself wouldn’t have become John Wayne Gacy? In the words of Christian martyr John Bradford, “there, but for the grace of God, go I.”

Near the end of the Bible, Peter describes Christ, using the words of the prophet Isaiah, as “a stone that causes people to stumble, and a rock that makes them fall.” Granted, it may not be the most appealing description of the Messiah, yet it is true none-the-less. Christ, God in the flesh, came to earth precisely because mankind, each and every one of us, are little John Wayne Gacys. Yes, the majority of us haven’t killed anyone, but in his most famous teaching, the Sermon on the Mount, Christ calls murder and hatred the same thing. “You’ve heard that it was said to the people long ago, ‘You shall not murder,’” Christ teaches, “But I tell you that anyone who is angry with a brother or sister will be subject to judgment.” In one fell swoop, Christ puts all of humanity on a level playing field, the murderer and the hater now one in the same, both with an equal (and colossal) need for a Savior – and this is exactly what makes Christ a “stone that causes people to stumble.” My human nature wants to look at John Wayne Gacy and see a monster, to know that I am incapable of the degree of evil that he carried out. And yet Christ comes through, uncovering the secrets I’ve stowed away under the floorboards of my heart, claiming that the murderer and I are sailing in the same boat, in need of the same thing – the healing touch of God Himself. For some people this truth is just too big a shot to their pride to accept, and they walk away from the only thing in this entire universe that can truly be called good.

As much as it may sound like a fairy tale, I truly believe we’re living in a world under a curse – that we were created good (as Mr. Reece believes) but due to our rebellion against God, we’ve fallen from that ledge, a height we’re unable to reclaim on our own. As Don Miller writes in Blue Like Jazz, we’re “broken… cracked, [unable to] love right, to feel good things for very long without screwing it all up… like gasoline engines running on diesel.” The Biblical writer Paul felt the same thing, “I find this law at work,” he wrote in a letter to the church at Rome, “Although I want to do good, evil is right there with me.” For an instant, the hopelessness of the situation overtakes him as he mourns, “What a wretched man I am! Who will rescue me from this body of death?” The answer to his question is hope for the entire world, from the mountains of eastern Kentucky, to a disenchanted college journalism professor; from a serial killer to a twenty-seven year-old kid from Danville – “Thanks be to God, who delivers me through Jesus Christ our Lord!”

To a dying world, those are the words of life itself.

Contrary to popular belief, the Bible isn’t a rulebook. Sure, there are some sprinkled here and there. And yes, one book (out of sixty-six) is devoted entirely to the “thou shalts” and “thou shalt nots.” But if you look closely, you’ll find the majority of the text is dedicated to something much more interesting and life-changing than a bulleted list of guidelines. At its core, the Bible is a story – the true tall-tale of a God who created and then rescued that creation from itself.

Why does God use story? Honestly, He could have saved a lot of time (and trees) if He’d have cut all that out of His book. But then, of course, we wouldn’t know about David, Noah, Paul, or even Jesus Himself. The four books that tell the story of the Messiah weren’t recorded as direct dictations, a list of His sayings, but rather as a story-line: He went here and did this, traveled there and said that, came over here and this happened. More than any other method, the God of the Universe uses simple storytelling to make Himself and His plans known.

In graduate school, as I was learning to become a teacher, I was repeatedly told that lecturing is one of the worst methods for conveying information. Most studies indicate that a student remembers approximately 20% of a lecture’s main points, let alone the fine details. For most of us, we just don’t learn that way.

If you could go back in time ten years and take a walk through the halls of Danville High School, one thing would stand out: the sleep-inducing glow of an overhead projector coming from nearly every classroom. Apparently my instructors missed the graduate school lesson on teaching methods, as lecturing was far and away the preferred technique when I was in school. To this day, the hum of an overhead projector fan makes my eyelids grow heavy.

But Mr. Trumbo – my freshman U.S. History teacher – he was different. Instead of messing with that “new-fangled technology,” he stood in front our classroom and told stories: Washington crossing the Delaware, Harriet Tubman on the Underground Railroad, the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the assassination of John F. Kennedy. These weren’t static events on a worksheet, but dynamic tales, masterpieces colored by my teacher’s words. I laughed. I learned. And I never, ever, fell asleep in his class.

Although he gets little respect from the critics, I’m not ashamed to say that M. Night Shyamalan is my all-time favorite filmmaker. You’re certainly free to disagree (and most people do), but I’ve always found his films challenging, insightful, and spiritually relevant. During the summer of 2006, his movie Lady in the Water debuted, telling the tale of a naiad-like character named Story. This sea-nymph is discovered in the pool of a Philadelphia apartment complex by its manager/landlord/handyman Mr. Heep, who then sets out to help her return to the “Blue World” from whence she came. As the film progresses, Mr. Heep realizes he needs help. Apartment complex residents of all shapes and sizes are brought into Story’s inner circle, each one discovering that they possess specific abilities to help her return home.

A list of rules does little to tell us who we are, why we exist, or that there is a God who loves and desires us. But a story, it can do all three. In Lady in the Water, the residents of the apartment complex only realize they are extraordinary when they come into contact with Story. From where I sit, the same is true of us, and this is precisely why I believe the God of the Universe uses stories much more than rules to teach us about Himself.

In Blue Like Jazz, Donald Miller has a similar experiencing, writing that it was story he once heard that helped to resolve some of his issues with God. That story is included below – and if you’re anything like me, you’ll find it a beautiful one indeed.

“A long time ago I went to a concert. Between songs, [the singer] told a story about his friend who is a Navy SEAL.

“The folksinger said his friend was performing a covert operation, freeing hostages from a building in some dark part of the world. His friend’s team flew in by helicopter, made their way to the compound and stormed into the room where the hostages had been imprisoned for months. The room, the folksinger said, was filthy and dark. The hostages were curled up in a corner, terrified. When the SEALs entered the room, they heard the gasps of hostages. They stood at the door and called to the prisoners, telling them they were Americans. The SEALs asked the hostages to follow them, but the hostages wouldn’t. They sat there on the floor and hid their eyes in fear. They were not of healthy mind and didn’t believe their rescuers were really Americans.

“The SEALs stood there, not knowing what to do. They couldn’t possibly carry everybody out. One of the SEALs, the folksinger’s friend, got an idea. He put down his weapon, took off his helmet, and curled up tightly next to the other hostages, getting so close his body was touching some of theirs. He softened the look on his face and put his arm around them. He was trying to show them he was one of them. None of the prison guards would have done this. He stayed there for a little while until some of the hostages started to look at him, finally meeting his eyes. The Navy SEAL whispered that they were Americans and were there to rescue to them. Will you follow us? he said. The hero stood to his feet and one of the hostages did the same, then another, until all of them were willing to go. The story ends with all the hostages safe on an American aircraft carrier.

“I never liked it when the preachers said we had to follow Jesus. Sometimes they would make Him sound angry. But I liked the story the folksinger told. I liked the idea of Jesus becoming man, so that we would be able to trust Him, and I like that He healed people and loved them and cared deeply about how people were feeling.

“When I understood that the decision to follow Jesus was very much like the decision the hostages had to make to follow their rescuer, I knew that I needed to decide whether or not I would follow Him.”

Challenge: To reread the three books which have made the biggest impact on my life,

faith, and understanding of Christ.

Why: To relearn, rediscover, and fall in love once more with the lessons, ideas and

stories that have made me the man I am today.

---

“I can’t imagine a man really enjoying a book and reading it only once.”

_C.S. Lewis

This month’s challenge started, as all great ideas do, with a tweet.

In my humble opinion (for whatever that’s worth), C.S. Lewis sits atop the list of the premier Christian thinkers and writers of the last century. Having read a majority of his work, both fiction and nonfiction, I find his gift for words both inspiring and challenging – and I am not alone in this. His influence on theology and apologetics is incalculable; his wisdom is quoted everywhere from blogs, to sermons, to billboards; his stories are so enchanted that, over sixty years since their initial publication, they remain classics of literature. Every word Lewis wrote was a gift – the kind that continues to give.

Clive Staples Lewis passed away on November 22nd, 1963. That same day, our thirty-fifth president, John F. Kennedy, was assassinated while traveling in a motorcade through Dallas, Texas. Though he’s been dead nearly half a century, Lewis’ popularity hasn’t waned. In fact, not even death could stop Jack (the name his close friends gave him) from embracing social media – he has three different Twitter accounts, used daily to impart his wisdom to the world (in a 140 characters or less, of course).

A few months ago, one of those Twitter accounts tweeted out a quotation from a letter Lewis wrote to his close friend, Arthur Greeves. Learning that Mr. Greeves wasn’t much of a rereader, Lewis took it upon himself to convince his companion that books were worth more than just one read-through. Rereading a familiar book, Lewis wrote, was “one of [his] greatest joys;” in fact, he “[couldn’t] imagine a man really enjoying a book and reading it only once.” Now that’s worth a retweet.

A few days ago, while spending some time at home, I asked my mother if she’d read a book I loaned her over Christmas. “Oh yes!” she replied emphatically, “It was so good!” A moment passed in silence before she turned and asked, “what was it about again?”

As much as I hate to admit it, I know exactly how she feels. In terms of rereading books, I’m much more like Arthur Greeves than the author I so admire – a deep passion for the written word, but with little motivation to reread them. Unsatisfied to remain in the ranks of the one-and-done readers of this world, July’s challenge has been designed to allow me to take Jack’s advice to heart, jumping right back into the books that have had the most profound influence on my life. And since I love to while away the afternoon with a book in hand, this challenge won’t be so much a trial as it will be a break, a great spot to rest as I approach the half-way mark of my Year of Change. What might surprise you, however, is that I didn’t always find joy in the written word – not by a long shot.

With all the loathing a high school student could muster, I despised summer reading. After nine months of slavery in the classroom, it seemed hardly fair that my teachers were allowed to ruin summer as well, forcing us to read books of their choosing. Like most high schoolers, I had a profound sense of justice, especially when it came to my rights. It sounds a bit dramatic, but the torture of having to spend my summers with Madame Bovary and Tess of the D’Urbervilles turned me off to reading. I could count on one hand the number of books I read for fun while still in high school – and the vast majority of those were probably about Star Wars.

College, thankfully, was a much different story – there, the women weren’t too impressed by a man who’d rather play video games than read, so the bookshelf started to fill up. And with all those books lying around, I might as well crack one or two of them open from time to time, right? I quickly discovered that books might not be so bad after all, and in time, I was devouring them, left and right. Over the course of a few years, I’d stumble upon three books that would drastically alter my thinking, lifestyle, and relationship with Christ. If it didn’t sound so sacrilegious, you might even be tempted to nickname them “the trinity,” – but since it does, forgot I even mentioned it.

Those three books gave me hope. They opened my eyes to the passions God’s placed within me, and imparted wisdom that’s forever altered the way I look at the world around me. Those books did nothing less than change my definition of what it means to actually be a follower of Christ. (Before I go any further, let me say that, by far, the most important book I’ve ever read is the story of God and man – the Bible. Without it as a foundation, as the backbone to everything I know, those other three books would be meaningless. Fortunately for me, that was not the case.).

Rereading is all about seeing the familiar with new eyes and a different perspective – to rediscover a truth that’s been buried under the sands of time, bringing that pearl of wisdom back into the light of day. I anticipate spending time with these books will be like visiting an old friend – as you greet, your instantly reminded why you love them, but as the hours pass and the conversation grows rich, you realize there’s so much more, layer of depth you’ve never bothered to notice.

But that’s enough jibber-jabber for now – it’s time to get down to business. What are the titles of these three mystery books, the ones I’ll be reacquainting myself with this summer? I could tell you, but that wouldn’t be much fun. So get your Slylock Fox magnifying glass out and do your best to crack the code. Here’s your clue – I’ve combined the titles from each book into one, new, super book name: “Blue Like Irresistible Christianity.” (Okay, I know that code is super easy to break, but cut me some slack, I’m a writer, not a spy). From here on out, when I need to refer to all three books, I’ll be using their new, collective name.

If you’ve been keeping up with my “Year of Change” challenges (or, if you’re an astute code breaker), you won’t be surprised to learn that Donald Miller’s Blue Like Jazz is the first volume on my summer rereading list. I’ve written about Don’s books and my affinity for them numerous times throughout the course of this year ( here & here, for example). I didn’t realize, when a friend handed me a copy of this book during my freshman year of college, that it would be the beginning of a long reading relationship – I’ve since moved through all his works and even had the chance to see him speak live. To this day, he remains one of my all-time favorite writers, a constant source of inspiration as I try to blaze my own trail with the written word. Interestingly, though, Blue Like Jazz isn’t my favorite of Don Miller’s books (that’d be a tie between A Million Miles in a Thousand Years and Through Painted Deserts) – it does, however, remain the most influential. College is the time when the rubber really begins to meet the road in a student’s life, and it was no different with me. It was at this crucial juncture that Blue Like Jazz entered my life and began to redefine for me what it meant to be a Christian. Don’s book was the first I’d ever read that wasn’t afraid to ask questions and not have all the answers, nor did it shy away from pointing out aspects of American Christianity that were causing me to shake my head as well. At a time when legalism threatened to wreck my faith, Don’s interest in following Christ more than the traditions of man was a breath of fresh air. As I started out in the world, a naïve nineteen year-old, this type of radical obedience to Christ was what I longed for – and, I’ll be honest, I also thought it was freaking cool that he wrote about Jesus and beer in the same paragraph. It was while reading Donald Miller that I first imagined that I could do the same thing – use words to express the lessons and truths that God was teaching me. It took me years before I’d actually begin, and even longer before I’d let others read hem, but the seed was planted and my love for writing has since grown into a marvelous tree. In fact, without Blue Like Jazz, I’m sure I wouldn’t be blogging right now, or working toward having my first book published. And while that’s all well and good, more than anything else, Don’s book taught me to own my faith, to examine it from all angles, to ask questions, to seek out answers (and not necessarily the easy ones), and to engage in the dirty work of following Christ with every step I take. I’m excited to spending time once more with a book that’s been so influential in my life. As I read through it, I’ll be sharing quotes, ideas and the new (and old) lessons God has in store for me. Stay tuned, this is gonna be one trip down memory lane worth taking.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed